|

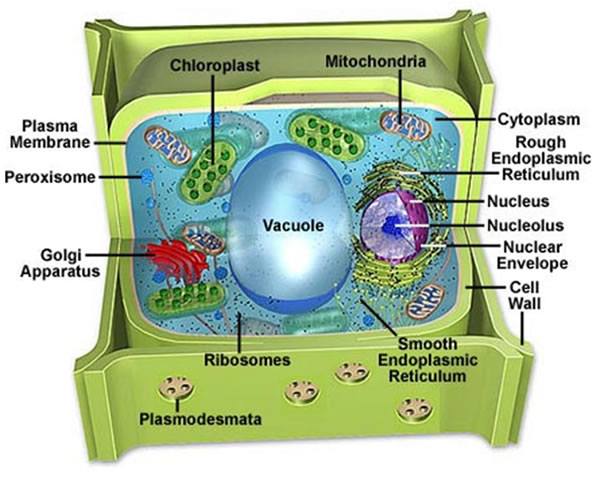

| Plant cell with vacuole in it |

Vacuoles are receptacles within plant cells that hold water, enzymes, eacids, waste products, pigments, or other substances that serve the plant.

Vacuoles are the largest organelles in most mature plant cells. Frequently constituting more than 90 percent of the volume of a cell, the vacuole presses the rest of the protoplasm against the cell wall. Vacuoles are surrounded by a single fragile membrane called the vacuolar membrane, or tonoplast.

The contents of the vacuole, referred to as vacuolar sap, is 90 to 98 percent water. The vacuole of a typical plant cell occupies approximately 500,000 cubic micrometers. It would take approximately two million of these vacuoles to equal the volume of a sugar cube.